I was born in Caracas, between the corners of Miseria and Pinto, in the Santa Rosalia Parrish, on March 20th, 1922.. Part of my childhood I spent in Valle Abajo (foto 01) an important sugar cane plantation in the valleys south of Caracas that today include the urban area of Santa Monica and part of Los Chaguaramos. The hacienda belonged to my grandparents Don Eduardo J. Sanabria and Carmen de las Casas de Sanabria. I have extraordinary, but limited, memories of Valle Abajo its environment was intimately linked to the presence of the majestic Avila (foto 02). I remember the family enjoying the exceptional view of the mountain and its streams. During the dictatorship of General Juan Vicente Gomez, Gomez wanted to buy my grandfather’s land and, as he was refused, General Gomez gave the order to close off the canals that irrigated the fertile fields. In spite of everyone’s efforts – my father sold his property in Aragua in order to save his father from this wrongdoing – nothing could be done and we all ended up ruined.

As a child I attended San Ignacio and La Salle schools (foto 03) and graduated from Andres Bello High School in 1940. I finished my studies enthusiastically especially since I had the good fortune to establish friendships that have lasted a lifetime. In high school, I became a citizen experiencing, together with my fellow classmates, the challenges of democracy for the first time. I felt the advantage of liberty versus the imposition of dogma. I understood the significance of respect and admiration of others. Years later some of my classmates held important positions becoming cabinet ministers and one of them even becoming the president of the republic.

The physical environs were conducive to appreciate simplicity and honor the value of function. I admired the dimensions of the main building of my high school, its height and the details of the stairs, etc. (foto 04)

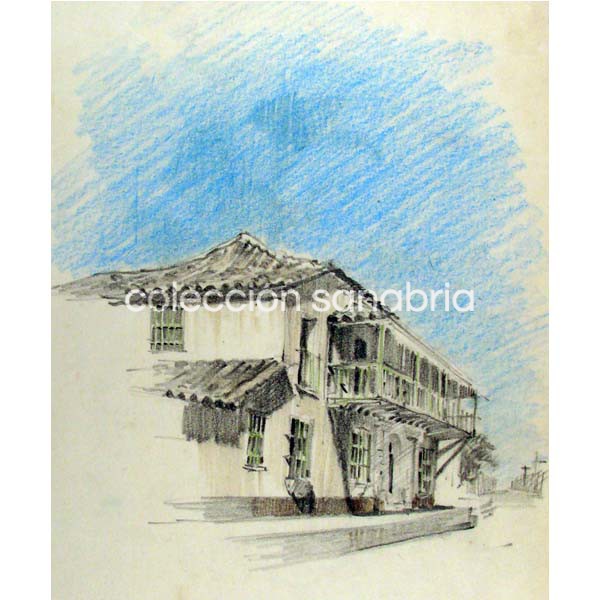

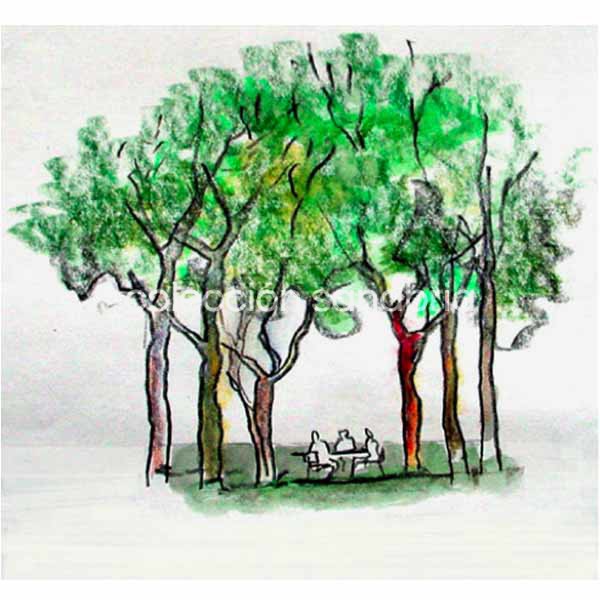

I remember in the forties I saved money to take a bus to Coro. Upon arriving I spent all my time drawing (foto 05 y 06) the beautiful architecture of our colonial period. At other times the trips were shorter to more nearby places with the same purpose.

My father was in agriculture and my uncles in business, therefore my interest in architecture was personal and direct, undoubtedly due to the curious and inquisitive personality that has always characterized me.

I learned a great deal from my uncle by marriage, Rafael Herrera Figueredo, while living in his home. He was a geological engineer, but over time and as a result of malaria contracted in the interior of the country, he worked as a civil engineer in important positions in the building department of the ministry of public works. He graduated in mathematical analysis, making extraordinary slide rules to simplify calculations, many of which were used to chart sun paths. He made the first slide rules of Venezuela’s coordinate system. He was a tireless investigator and my great interest in sunlight’s effect on buildings I owe to my uncle Rafael, taking into account the important role that the tropics play in architecture. I remember that he was both loving and demanding. I remember at lunch one day he told me “ from now on we should only speak in Morris Code” (a communications system developed at the beginning of the 19th century consisting of combinations of dots and dashes). For this reason I needed to study and be prepared. In fact we did communicate with Morris Code and enjoyed it for a long time! (foto 07)

When it was time for me to start the university, the field I had always thought I would study was not yet available in Venezuela. The establishment of architectural studies had been discussed for two years but had not yet been formalized For this reason, in 1941 I enrolled in the discipline that I considered the most similar, engineering, which I studied until 1945.

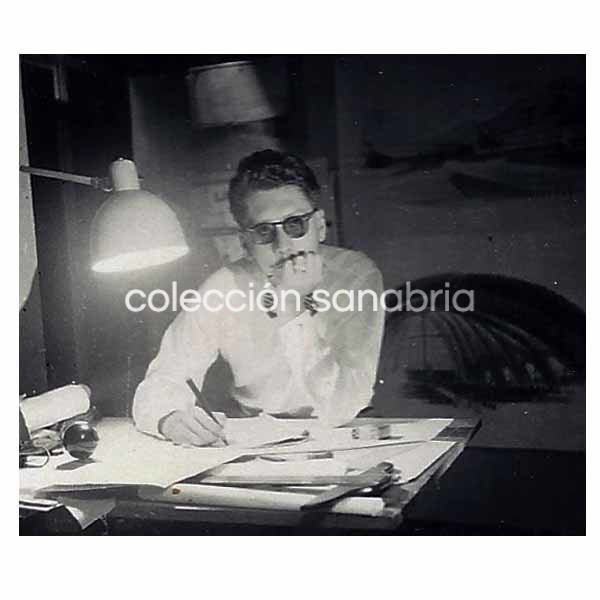

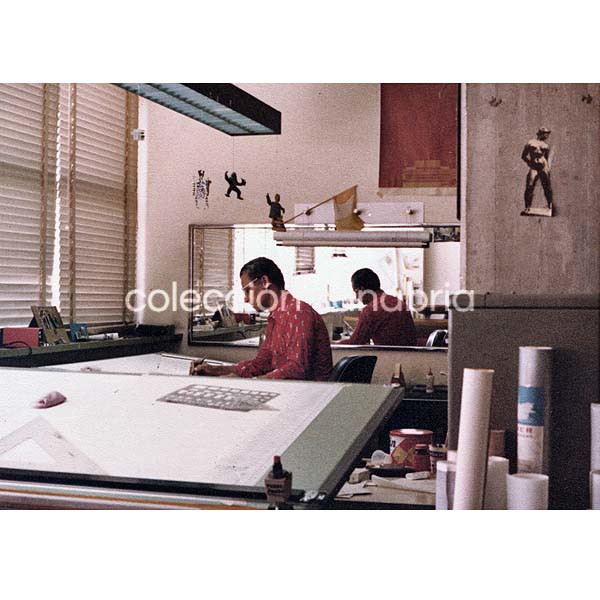

I learned a great deal studying engineering especially with respect to the technical aspects of construction but I had difficulty with pure math (especially with infinite calculus). Fortunately at that time I was working as a draftsman (foto 08) for the construction firm of Vegas and Rodriguez Amengual (VRACA) who gave me a scholarship to study architecture in the United States.

I was finally able to study my chosen career when I was accepted by the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University. This was during the war and at just that time the founders of the Bauhause School from Dessau, Germany had been exiled by the dictator Adolph Hitler because they were Jews. Harvard University contracted them and due to lack of jobs there were more professors than students. I had the great fortune to find myself in this situation – 28 professors for 25 students – circumstances in which we interacted daily with the great revolutionaries of contemporary architecture. .(foto 09).

I was the student of great professors such as Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer (foto 10 1), Martin Wagner, Hugh Stubbins and Ioh Ming Pei, (foto 10 2). Pei was at that time was studying for his master’s degree. This was a period of immense good fortune for me. I had the opportunity to participate in and understand the criticism and commentary during multiple working sessions where the illustrious professors discussed, in our presence, in the most simple and straightforward manner, the experimental changes that architecture was then going through (foto 11).

Returning to Venezuela in 1947, I continued working at VRACA in order to pay back in some manner the opportunity I had been given.. At that time the large department store SEARS was under construction. There I had my first opportunity to interact with the architects who represented the Chicago firm. Due to excessive caution, they proposed siting the building to one side of the property in order to leave the rest of the site for parking or future development in case the project failed. I proposed placing the building in the center of the property so that the parking was closer and more balanced for the user. (foto 12). At that moment, I believe, the conflict with which I have lived my entire professional career began – that disagreement which arises between those who see the value of the urban space and those who value the interests of the investor.

There was a competition for a large building that was to be built on the Salas corner. VRACA signed up and I fully immersed myself in the development of this project. VRACA won the competition even though renowned architects competed. The firm waited for the validation of my degree and made the gesture of publically honoring me with the award and the cash prize. The building was never built but without doubt the publicity was beneficial for me.

I did small residential design projects for people that had faith in me (the first was the house Casanay I, in Caracas, 1948). These accomplishments motivated me to dedicate myself completely to validating my degree (foto 13) and obtaining my Venezuelan architectural license in order to achieve my professional independence.

A few years earlier a group of architects including Carlos Raul Villanueva, Carlos Guinand, Luis Malaussena, etc. had arrived from the Beaux Arts in Paris and now they worked for the government…what hope then was there for us? (foto 14)

Three young architects each of us recently graduated from the United States got together – the architects Juan Andres Vegas and Diego Carbonell had both graduated from MIT University. Without wasting time we began to meet in discussion groups – ‘peñas’. Every Wednesday we talked. Worried about the future that awaited us, we analyzed the situation and how we could change it (foto 15). In the end it was not wasted time since as a result of these meetings three essential activities were initiated. Juan Andres later occupied positions of authority in urban planning on a national scale. Diego was interested in the profession and became president of the Venezuelan Society of Architects. I liked teaching and I had the honor to become the first director of the School of Architecture (F030).

During the time that I was the director of the School of Architecture of the Universidad Central, I felt an immense responsibility and satisfaction in doing this work. After a short time, I contracted for six months the architect George Rockrise (foto 16) from California to create a modern curriculum in accordance with our times. He worked on this but unfortunately when formally presented it was rejected due to disagreement that arose among those at high levels.

As an interesting anecdote, I am going to relate one worth mentioning. It came about between two very competent professors that for reasons better left unsaid came to blows. Unfortunately I had to resolve the situation in a drastic manner and had the disagreeable obligation to fire both professionals.

I spoke with the professor Abel Vallmitjana (foto 17), a respected friend, educated in history and the arts. After several meetings we collaborated to create an innovative way to teach the history courses doing so in an up to date manner that was very well received by the students. We agreed to start the discourse from the present back to antiquity; the reverse of what was the practice at the time. I was pleased because the proposal was very successful and its acceptance also indicated that our youth were open to change.

It was necessary to make modifications in a field that clamored for new ways to approach problems…change was inevitable.

It was a small school with a limited curriculum. Without a doubt it was an interesting challenge and I wanted to express the interests that I had acquired in Harvard. The situations in which I found myself led me to develop organizational schema, which I elaborated on over time and in response to the needs of the school. I considered it indispensable that the school had a limited enrollment in order to facilitate a direct relationship between director, professors and students.

The architect Julián Ferris won the first election and I advised him not to allow the school to expand to more that 400 students. I heard that at one point it had 4000!

A school without controls becomes larger and larger, losing its ability to have interaction between learning levels, to establish mixes in related subject matter, and to maintain unity and values that facilitate teaching. I am aware of cases in which students do not know each other or their professors, where they never have had contact with educators that exposed them to new ideas. It’s much better to have several competing schools with few students than a gigantic one that is less effective.

We were trained at Harvard to work based on a master plan; this was not yet the case in Venezuela. I remember having the good fortune to have had marvelous conversations with Carlos Raúl Villanueva at the time that he was being required to increase the number of buildings of the university beyond that which he could accept. As master planning was not an established practice, he was not supported in his objections.

During my time as director, I maintained a close relationship with the professors working with me, partially through weekly meetings for the advancement of the school and its evolution. Actually this was one of the reasons that initiated my leaving. I remember that I almost fought with the architect Willy Ossott (foto 18), who was the dean of the faculty of architecture, because he told me that for political reasons, no more than three of us at a time could meet.. So I convened all of the professors, about ten, to my house to continue to meet our responsibilities. The next day I received a reprimand mandating that it not happen again. How can one administer an educational center with these kinds of restrictions?

As a professor in the design studio, I was concerned with the increasing size of the student body and the resulting creation of new studios, while at the same time the actual teaching was getting away from us.

I began to withdraw from the University in order to dedicate more time to my office that was requiring more effort. I had to do it in order to respond to many commitments. But I need to mention that my previous focus on the university was now transferred to my first office of architecture that I had established with Diego Carbonell (foto 19)

When you teach, you learn more as a professor than you end up teaching as a teacher. To see multiple pairs of eyes concentrated with interest on what you are saying is stimulating. With intelligent questions new ideas are proposed that make one think and learn.

I have always felt an obligation to speak with students – it gives me great satisfaction, and for this reason, I have shown students my interest in them both at the university and from my office.

In 1949, I established with Diego Carbonell the first architectural practice in Venezuela, Carbonell & Sanabria. Our partnership lasted until 1953. The first office was located in a penthouse south of the Teatro Municipal (Calle 08 bis). After one year we moved to the Araure Building on Sabana Grande (foto 20).

All I remember is criticism from all I announced our plan to – they said it was a crazy thing to do. At that time there were several engineering offices whose existence was due to an intelligent and timely idea of the engineer Gerardo Sansón (foto 21). the Minister of Public Works. The custom at the time was for the government to contract its major engineering projects with large foreign firms. Gerardo, wisely and justly, divided into several segments the new highway connecting Caracas with Puerto Cabello, assigning the construction of the segments to new Venezuelan engineering firms like VRACA. In this project, as well as in the redevelopment of El Silencio, the engineering firms were able to synthesize the essential elements of the system in a unifying way. This is how engineering started in Venezuela!

Months went by without a single call. We had agreed that we would not draft a single line without signing a contract establishing an initial payment. Finally we received a call from the Venezuelan industrialist, Carlos Degwitz, who wanted us to design his house in Valencia. This was the start of our activities and demonstrated that our venture was not crazy.

In 1953, Diego and I broke up the firm. I established the office under my name Tomás José Sanabria, Architect, in the new Polar building in Plaza Venezuela (foto 22).

In 1963, I decided to invite my brother Eduardo who was also an architect to become a partner. We founded the office Tomás José Sanabria and Eduardo José Sanabria, Architects, which lasted until 1972. The first years we stayed in the Polar Building and then we moved to Santa Monica. (foto 23).

In 1972 we changed the name to Sanabria Architects, S.A. until 1989, when for personal reasons, Eduardo separated from the firm.

At that time I invited the architect Gustavo Torres B., who had been working with us for years and Lolita Sanabria, my daughter and an industrial designer, to form part of Sanabria Architects, SA (foto 24).

We maintained this firm on Sabana Grande until 1999, when a new crisis started in Venezuela.

In 1999 Gustavo became independent from the firm and I continued with Lolita my daughter the office of Sanabria AA, C.A. on Sabana Grande and later in the CCCT, where we are still located (foto 25).

Next year I will mark 60 years since establishing that first architecture office. We have been through years of severe economic crisis where the majority of architecture firms have closed their doors. I’ve known how to maintain my office – with different names over time – always active until now (October 2008).

Speaking with students I feel is an obligation that has given great satisfaction because it is like talking with the future.

In my office I have stayed in contact with all the students that have so desired. The doors to my Shop were always open. I have given them the attention that students from any university deserve. With great enthusiasm I have accepted invitations to give lectures at schools both here and abroad. I believe I have continued my work as an educator both in the university classroom as well from my office, and as long as my health permits my goal is to continue doing it.

I have accepted projects of many different scales but I have also rejected those that I would not have been able to properly complete or whose complexity conflicted with current projects.

In all the stages of my architecture office, I have been clear that I didn’t want to grow to the point of losing control, as my work has always been personal. I have received offers from abroad that out of principal I have refused. As an exception I should mention a house I designed in Bermuda, for which I traveled to the site and stayed there for two weeks in order to understand the norms and customs of the area.

There is a saying of the writer Ana Nin that I like for its clarity!

WE DON’T SEE THINGS AS THEY ARE

…. WE SEE THEM AS WE ARE!

The training of architects in the office was a profound and extensive educational task. It took a couple of years for a recently graduated colleague to understand and immerse himself in the philosophy of the Shop. His first job upon becoming part of the team on a specific project was to understand the space. I explained to students the importance of the urban space, asking them to go to the site, smell it, feel it, see how it changes during the day, the night, with rain, on workdays and holidays, at different times of day, etc. For many young people this might seem a waste of time and even, slightly offended, they prefer to give up. But little by little, those that possess the discipline and strength become true collaborators producing the information required to design the proper responses. The Sanabria office has always had an atmosphere of great fellowship. I have been fortunate to rely on people for long periods of time, Agurne Badiola for 51 years (foto 26). José Antonio Diaz M. for 48 years (foto 27), Alfredo Hernández up to his death for more than 40! (foto 28)…. … without naming everyone, I can gratefully affirm that this human and professional team has been extraordinary. (foto 29 1).

Teaching and learning from workers, foremen and technicians has been indispensable for me. Sharing experiences with them helps me work out how to get things done in the best possible way. (foto 29 2).

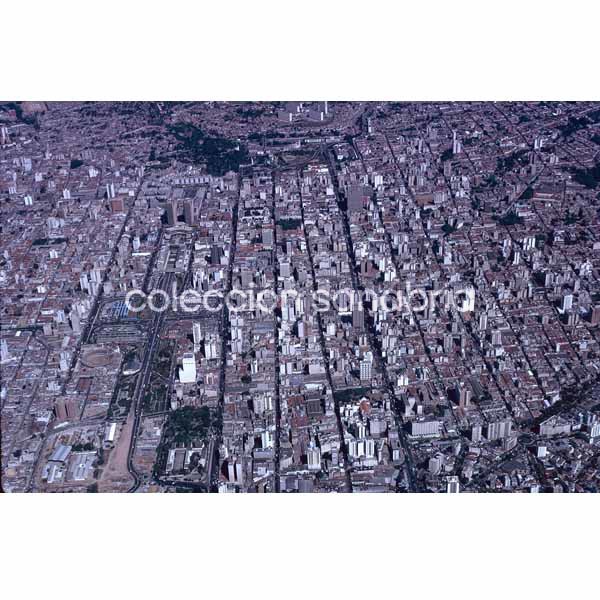

Through the years, I was offered government positions like the Minister of Public Works or President of the Simon Bolivar Center, positions that I did not want to accept due to my obligations to the office. In 1964 I enthusiastically accepted the position of consultant to the Office of Urban Planning (OMPU), which I held until 1966 along with the architects Victor Fossi and Omer Lares. When I was in the OMPU, I remember that I asked for plans of the area of the city that we were working on. I was brought obsolete plans and graphics that did not serve our needs. I proposed that it was indispensable for the OMPU to have access to a helicopter to demonstrate the changing morphology of the city. (foto 30).

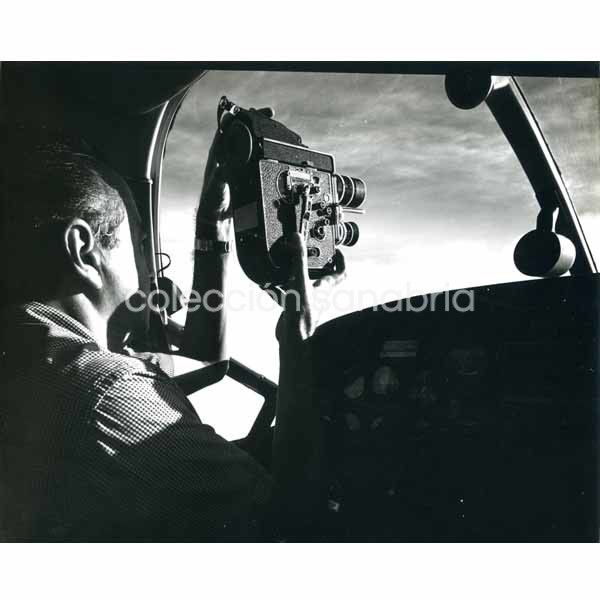

I have always enjoyed aviation – I was a pilot for some 30 years. I had the opportunity to have my own plane so that, along with the pleasure of flying, I was able to take area photographs develop and blow them up in time to have current material for the next meeting (foto 31). This convinced me of the value of photography and that was when I started my collection of aerial slides of the valley of Caracas and its surroundings. This extraordinary collection consists of more than 7,500 catalogued slides with descriptions of their content and stored in climate controlled conditions (foto 32). This material accumulated over so many years will become part of the Sanabria Collection to motivate and inform future generations.

The Sanabria Collection

I never thought that the materials used for analysis of projects, urban design proposals, protests against injustice and social inequity in the city, or just spontaneous reactions to a site visit could become in the future part of a collection such as that which we are currently putting together in the Casona de la Vega, whose custodian is the Alberto Vollmer Fundation (foto 33)

Certainly I preserved in good order all the photography, documents and drawings from my professional career as my personal philosophy is that the projects continue to be my professional responsibility. I have been fortunate to complete projects whose stages have lasted fifty years – the Electric Utility Company of Caracas, the Central Bank of Venezuela need arises – INCE, Caracas Airport OMZ, National Library and National Archives, etc. Therefore, to be able to count on historical information is critical.

The collection also includes difficult or painful cases, where human neglect and political irresponsibility has resulted in the loss of marvelous opportunities for renovation and revitalization of urban areas – Panteón Boulevard, or the Avila complex, etc.

Many of these circumstances and frustrations have inspired me to analyze and propose theses to be explored in the future. I am an optimist by all accounts and I believe that the climate of Caracas is the envy of any city. This is why I have formulated proposals such as the Stream Restoration Thesis T05, Caracas as an Olympic Host City Thesis T11, Avila Peak Thesis T00, Caracas in Fifty Years Thesis T54, Second Level Thesis T01, etc.

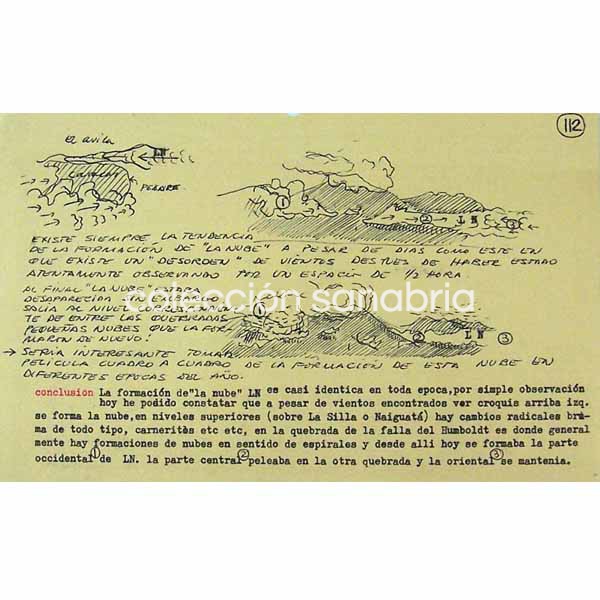

It’s essential to awaken and maintain interest in the city. We cannot continue just contemplating our navels. Immense amount of climate analysis have allowed me to know and respect our valley (foto 34). At this moment in time there is once again an opportunity and a responsibility for me to continue my work as an educator through analysis, theses, dissent, projects and proposals that will serve as a stimulus for future generations!! (foto 35))

(Written by Sanabria in October 2008)

(translated by Michelle y Antonio Violich 2010)